| Revivals

in the 13 Colonies in the mid eighteenth-century, which offered the

"New Birth" through evangelical preaching. |

|

|

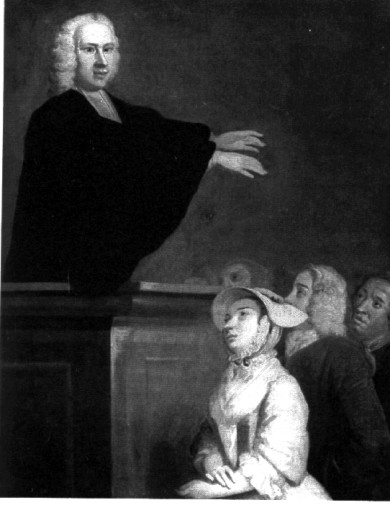

George

Whitefield preaching

|

For classical Puritanism,

conversion was the entry point into the Christian life. In the early 1700s,

however, few young people claimed such an experience and colonial pastors

lamented the "extraordinary dullness" in religion. In 1734 the preaching

of Jonathan Edwards sparked an intense

local revival in Massachusetts. The Awakening spread more widely with

George Whitefield's preaching tours of the Colonies,

beginning in 1740. Preaching from Georgia to what is now Maine, Whitefield

moved his hearers to repent and convert to faith in Christ. Whitefield's

hearers would shout, groan, or faint with the pangs of New Birth. Soon

many traveling preachers were imitating Whitefield. But the Awakening

had many foes, including educated, traditional clergy, some of whom were

influenced by Deism. Opponents of the Awakening

objected to "disorderly conduct" such as women speaking in public. The

issue of whether or not a minister needed to have a conversion experience

was hotly debated. For many, the Awakenings redefined ministerial authority:

what mattered was not formal education or a traditional call to a "settled"

parish, but the minister's own conversion experience and ability to convert

others. The Great Awakening made the New Birth a focal point of American

Christianity; this has been carried on by evangelicalism.

|